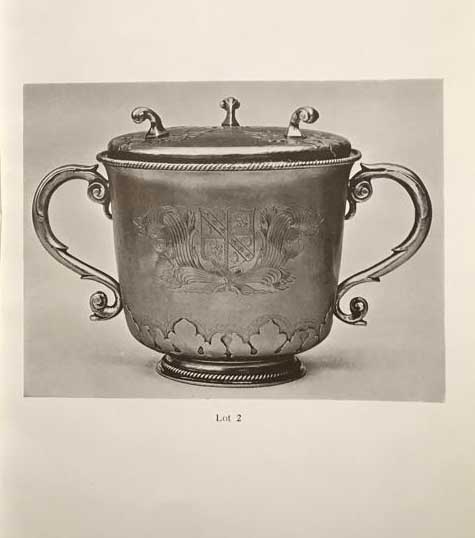

SAMUEL PEPYS: A HIGHLY IMPORTANT CHARLES II SILVER ‘TRENCHER PLATE’

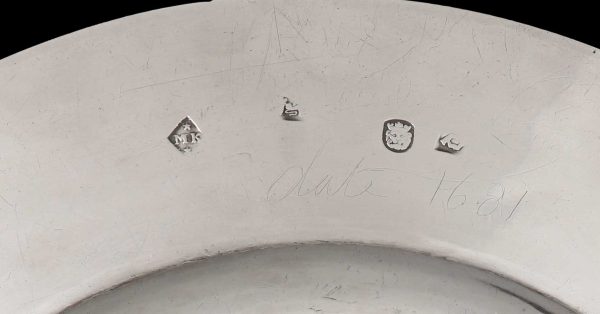

Plain circular with a wide reeded border engraved with a contemporary coat of arms of Pepys quartering Talbot for Samuel Pepys (1633-1703), within a shield between tied plumes and foliate mantling. Maker’s mark MK with a mullet above and below in lozenge shaped shield (see Jackson, 137), London 1681-2. Diameter: 10 3/4 inches; weight: 17oz.

AN EXCEPTIONAL PERSONAL RELIC OF ONE OF THE MOST CELEBRATED FIGURES IN LITERARY AND ENGLISH HISTORY

This newly-discovered silver plate belonged to the famous diarist and naval administrator Samuel Pepys (1633-1703). As he grew in wealth and status Pepys, the son of a tailor and laundress, attached importance to his use and display of ‘a very handsome cupboard of plate’ as a means of projecting his rising status. Reviewing his social progress on New Year’s Eve 1666, Pepys proudly confessed to his diary that ‘One thing I reckon remarkable in my owne condition is, that I am come to abound in good plate, so as at all entertainments to be served wholly with silver plates, having two dozen and a half’.

His enthusiasm for plate, whether gifts or purchases, is reflected with seventy mentions in the Diary, not least as a convenient and useful way of utilizing his savings. On 10 February 1662/63 Pepys had noted acquiring a silver cup ‘with my armes ready-cut upon them’ … ‘which is a very noble present, and the best I ever had yet’. In addition to his personal silver, used daily by the diarist, Pepys presented a magnificent silver standing cup, dish and ewer to his livery company at Clothworkers’ Hall.

The arms Samuel Pepys used are those of Pepys quartering Talbot for the marriage of Samuel’s grandfather to his grandmother Edith, daughter and heiress of Edmund Talbot. Pepys also displayed his coat of arms as they appear on this dish on many of the bindings and armorial bookplates in the celebrated Pepys Library at Magdalene College, Cambridge.

A stained-glass window dated 1677 at Clothworkers’ Hall in London commemorating Pepys’ role as company master and benefactor is similarly decorated.

This plate was acquired after Pepys closed his diary in May 1669 fearing its ill-effect on his eyesight.

As many of his personal belongings were destroyed in a fire at his home in Seething Lane in 1673, it may have been purchased as he replaced his lost collections. A footed silver salver dated 1678-9 [Clark Art Institute, Williamstown, Massachusetts, 1955.298] and a silver porringer dated 1671 [current whereabouts unknown] are the only other known examples of silver from Pepys’ private collection.

Both were sold by auction at Sotheby’s in 1931 having descended in the Pepys Cockerell family through Samuel Pepys’s nephew and heir John Jackson (1673-1724), and the marriage of his daughter Frances to John Cockerell of Bishop’s Hall, Somerset. The salver has the same reeded border as the plate and all three items show identical armorials and mantling.

Much of Pepys’ personal silver was acquired from his friend, the goldsmith-banker Sir Richard Hoare (1648-1719). Surviving accounts at Hoare’s Bank show his numerous purchases of silver from Hoare’s goldsmith premises at Cheapside from the early 1680’s. Richard Hoare’s ledgers detail how his silver was often decorated with ‘Coates and compartments’, or ‘Cyphers wth palmes’. The 1693-98 account book of the specialist engraver Benjamin Rhodes, who carried out much of Richard Hoare’s work, is preserved in the Hoare’s Bank archives.

It features a distinctly Carolean design for arms that closely matches the arrangement of the arms on the celebrated Pepys Cockerell footed salver and porringer as well as the present Pepys’ plate. Interestingly, this design appears Stuart in style, and thus old fashioned, as opposed to the many William and Mary armorial drawings that populate the account book. If not an aesthetic show of allegiance to his Stuart masters, Pepys’ continued use of same engraving style is consistent with a mind attuned to organizational uniformity.

Hoare’s ledgers also reveal Pepys’ putting his affairs in order at the bank shortly before his death with the sale ’34 Trencher plates’ to Richard Hoare, and a further ‘2 boxes [of silver] Rapt up in sacking’ put into store at Hoare’s premises. These deposits if in settlement of his account may explain the great scarcity of Pepys’s personal silver, while verbal bequests by Pepys of plate to the value of 50l each to his protégé and heir John Jackson, to his old friend and executor Will Hewer and his housekeeper and probable mistress Mary Skinner, hint at the survival of more than the footed salver and porringer sold in 1931 [Tanner, J.R. (ed) (1926), Private Correspondence of Samuel Pepys, 1679-1703’, pg.318].

The maker’s mark ‘MK’ in a lozenge between two mullets, is that of Mary King, one of only 63 women identified as being engaged in the London silversmithing trades between 1200 and 1800 [Heal, Sir A. (1935), The London Goldsmiths]. She was the wife of plate worker Thomas King who dwelt and carried on his business from a house in Foster Lane close to Goldsmith’s Hall.

Following his death in 1680 Mary continued his trade, most probably as a subcontractor to a number of retailers and goldsmith-bankers. She was granted a connection with the Goldsmith’s Company ‘by courtesy’, allowing her to inherit her husband’s apprentices and to register a maker’s mark in the shape of a lozenge, the heraldic shape for a widow. Mary appears to have died in August / September 1685. Her mark also appears on two silver communion cups dated 1683-4 [V&A, London].

Purchased in 2019 by the Museum of London.