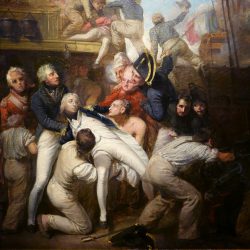

Re-discovered painting of the death of Nelson

The Death of Nelson, 1805

Samuel Drummond (1765-1844)

Oil on canvas, framed, 52 x 62cm.

Probably Royal Academy, London, Summer 1806 (catalogue number 505), as Sketch for a death of Lord Nelson

Private collection, Somerset.

This vivid image might be considered the earliest artistic reaction to the death of Nelson at the Battle of Trafalgar on 21 October 1805 news of which reached London in early November. Aware of its commercial possibilities, painters and their engravers in London had eagerly awaited details of this seismic event which so gripped and traumatised a nation. However, it seems none was quicker to his canvas than Samuel Drummond a seaman turned artist who, familiar with life in a British warship, grabbed the chance to steal a march on his rivals. Drummond would return repeatedly to this profitable subject over the next twenty years, yet it appears that this is his very first and, in many ways, most interesting effort. Urgently sketched in oils, the painting contains telling errors hurriedly discarded as more accurate accounts of the action filtered back to England with returning officers.

Self-taught and from rebellious origins—his father had distinguished himself in the Jacobite cause— Drummond was often at odds with the artistic establishment. John Constable referred to him as ‘the king of a Pot House, [with] such low habits & notions that he seemed unfit to be associated with men of rank’. Yet he carved out a successful reputation in portraiture assisted by a natural facility but also by his speed of working which could see him complete a portrait in oils at one sitting, at low cost to his customers. Prior to Trafalgar, he exhibited many portraits at the Royal Academy including of naval officers such as Captain Sir Sidney Smith (1795) and Admiral Sir John Borlase Warren (1798). In 1813, he would show a portrait of Nelson’s daughter Horatia indicating a connection with her mother Emma Lady Hamilton, who may have admired this representation of the death of her lover.

Despite modest commercial success in portraiture, it was as a history painter that Drummond (and many of his contemporaries) wished to be remembered despite having no patrons and, lacking a formal education, a scarcity of subjects. Early clumsy attempts included scenes from Shakespeare, Ovid and the Old Testament. Trafalgar, however, offered him the perfect opportunity. Aged fourteen, Drummond had gone to sea in the merchant service although it was claimed he also saw action with the Royal Navy during the American War (a boast he may have perpetuated for commercial gain). His experience at sea had already been recalled for a series of dramatic shipwreck paintings by Drummond, including The Drowned Sailor (exhibited 1804), and it gave his depiction of the death of Nelson a vital, visceral credibility lacking in the efforts of his competitors.

Working on patchy intelligence, in this earliest version of his Death of Nelson Drummond places the viewer on the main deck looking aft towards the quarterdeck and over the larboard rail where the stern of an enemy ship can be seen wreathed in smoke as she strikes her colours. This event is hailed by a British sailor on the rail who raises his hat in celebration unaware that behind him his commander has just been struck down by a musket ball. A bloody wound stains Nelson’s chest in accordance with the then belief, revealed by First Lord of the Admiralty Lord Barham in his letter of condolence to Lady Nelson, that Nelson ‘fell by a musket ball entering his chest’. In a scene deliberately reminiscent of the Pietà, Nelson is shown cradled by an officer and two tars, assisted by an officer of marines. His hat and fallen sword lie at his feet. With his dying look Nelson searches for another officer, identified as Captain Masterman Hardy, who gestures with his sword towards the defeated enemy. Oblivious to the scene unfolding beside them, a gun crew crouch and aim their next shot whilst the strangely truncated figure of a powder boy watches on.

Cleaning and conservation of the painting has revealed numerous re-workings as Drummond pressed to complete it as quickly as possible before passing it for publication as a coloured mezzotint by the entrepreneurial engraver William Barnard. As his aim was to scoop his rivals, speed was of the essence and it seems Drummond trusted to the engraver to tidy up his sketchy work. Barnard had issued four other popular portraits of Nelson since 1798, some with Lady Nelson’s permission and almost ‘official’ in nature, so like Drummond he clearly felt a need to rush out a print now. His involvement is a further indication that Drummond enjoyed special access to Nelson’s circle.

As hoped, Barnard completed the complicated task of converting Drummonds oil sketch to a mezzotint engraving with expensive hand colouring at breakneck speed publishing the image on 10 December 1805. This was barely a month since news of the battle reached England and just days after Nelson’s flagship Victory moored in the Thames, with the admiral’s decomposing body still stowed aboard. The only significant alteration Barnard made to Drummond’s oil sketch was to remove the wound from Nelson’s chest as it was now known that the fatal ball had entered his shoulder from above.

The painting and its print was obviously a commercial success although Drummond’s method divided critics with one complaining that his style was ‘slovenly’ and ‘dabby’. The Times, however, was fulsome in its praise noting that ‘Mr Drummond having himself served in the navy for upwards of seven years may fairly be presumed to be in his own element, and we may follow him with the utmost confidence to the very spot where the catastrophe befell the Heroic Nelson, and which made the nation weep!’ Sketch for a Death of Nelson was exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1806—when William Barnard re-issued his popular mezzotint in monochrome—with Drummond returning to the subject at least seven times over the following years, sometimes shifting the perspective and even experimenting with placing the viewer below decks as Nelson was brought down the aft hatchway ladder. Today, larger versions and variations of this original Sketch are in the collections of the National Maritime Museum, Greenwich (3); The Castle Museum, Norwich and the Government Art Collection (2). The Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool also has a large version exhibited by Drummond at the British Institution as late as 1825 by which time his collaborator Barnard held an official post in this important artistic organisation. All these later works include the unknown powder boy, his face obscured and who may represent the mute presence of the artist. None, however, show Nelson’s sword by his feet as the original does, as it had since become known that the admiral had left his weapon in his cabin on the morning of the battle, never to return.

Sold to a UK private collector