Oliver Cromwell’s Watch

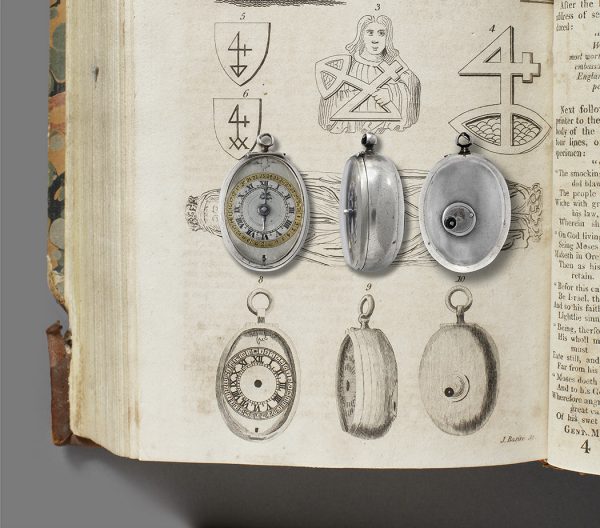

A mid-17th Century Puritan silver fob watch by William Clay, circa 1645, verge movement with gut fusee and worm-and-wheel set up, the top plate with pierced balance cock engraved William Clay fecit, supported on truncated pyramidal Egyptian pillars, the circular face having a single steel beetle hand, Roman numerals and 15-minute chapter within an outer gilt-metal calendar ring, the date indicated by an engraved hand, in an oval silver single case with shuttered winding aperture verso.

Dimensions approx.: 31 mm x 25 mm; 1 ½ x 1 inch

Towards the end of 1647 and the first English civil war, Oliver Cromwell moved his family to King Street in Westminster to ‘an old wooden house lying between the Blue Boar’s Head Yard and Ram’s Mews’.[1] This ancient street, overhung by timbered houses and gated at both ends, ran from Whitehall Palace to Westminster Abbey. It was a bustling thoroughfare between court and parliament and the move reflected Cromwell’s political ascent after his distinguished military service in the war. The street was narrow and dirty but prosperous with a half a dozen taverns and ‘houses [which] rose up three and four stories high; gabled all, with projecting fronts, story above story, the timbers of the fronts painted and gilt, some of them with escutcheons hung in front, the richly blazoned arms brightening the narrow way.’[2] The street’s proximity to power had attracted many prestigious and celebrated residents, such as admiral Lord Howard of Effingham and poet Edmund Spencer, and luxury shops to cater for them. Among these from 1646—just a year before the Cromwells moved to this same street—was the workshop of watchmaker William Clay. Clay was never a member of the Clockworkers’ Company—although it appears he became embroiled in a dispute at the Company in the 1650’s—and little is known of his career except as a skilled maker of lantern clocks and watches. He was also commercially astute, moving with the tumultuous times he lived in. And so, a luxurious and vibrantly enamelled gold pendant watch he produced for a wealthy customer in 1630, during the reign of Charles I,[3] contrasted starkly with the ‘Puritan’ style silver verge watch which his neighbour Cromwell acquired from him during the interbellum. Cromwell wore the watch, which is unusually small, on his fob chain (such a chain, associated with Cromwell, is in the collection of the British Museum[4]). In 1649, Cromwell led the New Model Army on campaign in Ireland where he presented the watch—at the siege of Clonmel in 1650 according to family tradition—to John Blackwell, deputy treasurer-at-war and an officer in Cromwell’s cavalry, known as the ‘Ironsides’.

It has been said that ‘Personalia with a robust provenance associated with Cromwell is so rare as to be virtually non-existent’.[5] Eleven watches have claimed ownership by Oliver Cromwell of which this example—and a near identical watch in gold by Robert Grinkin, circa 1640, gifted to the British Museum in 1786—are considered to have the best provenance to the Lord Protector. A survey of the watches in 2004 discussed the watch but noted that ‘unfortunately its present whereabouts is unknown’. [6]

John Blackwell (1624-1701), to whom Oliver Cromwell gifted his watch, was the eldest son of John Blackwell (1594-1658), a wealthy London merchant and grocer to King Charles I with strong puritanical ideals. In 1642, Blackwell senior was made captain in the fourth, or ‘Blew’ regiment of the City Trained Bands for the defence of London, with his eighteen-year old son John as an ensign in same regiment. Within a year, Blackwell junior transferred to the cavalry as cornet in the City Horse, otherwise known as Colonel Harvey’s regiment. In April 1644, to bring the regiment to a full strength of six troops, the parliamentarian newspaper Mercurius Civicus announced that: “the well affected Maidens in and about the City of London . . . are now collecting what quantity of money they can amongst themselves for the raising and setting forth of a Regiment of Horse”.[7] Young Blackwell was given command of this “Mayden Troupe” adding to the sum raised by the women, which fell short, with eighty pounds of his own money for the purchase of pistols for his 47 troopers. The troop mustered in May 1644 beneath a standard emblazoned with the city walls and flaming silver hearts. It then joined the Earl of Essex’s army for the summer campaign in the south west of England suffering heavy losses at Lostwithiel and Plymouth. Although Blackwell narrowly escaped capture by Royalist forces, the Maiden Troop was disbanded and its survivors dispersed to other units.

Portrait of a Man with a Watch, 1657, Cornelis Jonson van Ceulen the Younger (Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York).

Despite the loss of his troop, Blackwell remained a highly regarded officer who secured a new command in Cromwell’s own regiment of horse, the ‘Ironsides’, following the death of Captain Bush at the Battle of Naseby on 14 June 1645 at which it appears he was also present. In a sign of further favour, Blackwell was appointed deputy treasurer-at-wars, a role he combined with his military career.

The Ironsides accompanied the New Model Army to Ireland in 1649 where Cromwell gifted Blackwell his watch at the failed siege of Clonmel in April-May 1650. Blackwell marriage in 1647 to Elizabeth Smithsby, a relative of his stepmother and a cousin of Cromwell’s, had strengthened ties of kinship between the two men, giving reason for the gift.

Blackwell remained at the Treasury during the Protectorate rising to co-treasurer and sitting as a very active member of the Military Party in parliament. In the letters patent issued by Oliver Cromwell confirming Blackwell’s promotion, the Protector declared his “special trust and confidence in your fidelity and diligence and having good and sufficient experience of your abilities to discharge this great trust and service to which we have designed and appointed you”.[8] In 1653, as a judge in the High Court, Blackwell tried and sentenced to death the ringleaders of an attempt to assassinate Cromwell. Five years later, he followed the effigy of the Protector from Somerset House to Westminster Abbey during Cromwell’s state funeral. Nevertheless, as a member of the republican faction, he was then instrumental in seeing Cromwell’s son and successor Richard overthrown and the Commonwealth briefly restored.

Despite his intimacy to Cromwell and his high-ranking status, Blackwell survived investigation after the Restoration but was permanently excluded from office, leaving for America in 1684 with his second wife, a daughter of the celebrated republican general John Lambert. They settled in Massachusetts Bay where he was offered the governorship of Pennsylvania by William Penn. Frustrated in this difficult post, Blackwell resigned and, in 1693 or 1694, returned to England where he died at Bethnal Green in 1701.

Blackwell and his father had both invested as adventurers in Ireland ahead of Cromwell’s campaign and were rewarded by parliament with extensive lands in Dublin and Kildare. At the Restoration, his church and royal lands were forfeited but he retained estates at Ballyloughnane where his eldest son William settled, another son John having remained in London as a merchant. In Ireland, the Blackwells transmuted into the Bagwells whereas the English branch of the family retained the family’s original spelling.[9] Colonel John Bagwell (1751-1816), owner of Cromwell’s watch by 1808, was the great grandson of William Bagwell of Ballyloughnane. In 1808, Colonel Bagwell showed the watch to Richard Gough (1735-1809), a respected antiquary and author of A short genealogical view of the family of Oliver Cromwell. To which is prefixed, a copious pedigree (London, 1785). Gough arranged for Cromwell’s watch to be sketched, in three positions, before submitting the drawings, under the pseudonymous initials “P.Q.” for publication in the Gentleman’s Magazine.[10]

Cromwell’s watch today, superimposed on its illustration in the Gentleman’s Magazine in 1808

The watch then disappeared again from public view until December 1914 by which time it had descended to Colonel Bagwell’s great great-granddaughter Elizabeth Langley (1864-1953), wife of Edward Theodore Alms of Taunton. In 1914, Mrs Alms lent the watch to Somersetshire Archaeological and Natural History Society for exhibition at Taunton Museum where it was photographed and published by The Connoisseur magazine in 1919.[11] The watch remained in the family by direct descent until sold by auction in 2019.

Timeline:

1646: Watchmaker William Clay establishes his workshop in King Street, Westminster

1647: Oliver Cromwellmoves his family from Holborn to King Street.

He acquires the silver cased Puritan style fob watch from William Clay.

1649: Cromwell leads the New Model Army in the Parliamentary invasion of Ireland.

1650: At the siege of Clonmel, Cromwell gifts his watch to deputy treasurer-at-war John Blackwell.

1653: Cromwell made Lord Protector.

1658: Cromwell dies.

1808: Watch published in The Gentleman’s Magazine.

1914: Watch exhibited at Taunton Museum.

1919: Watch published in The Connoisseur.

2019: Watch sold at the Laidlaw saleroom in Carlisle.

[1] Walter Thornbury, ‘Cross Country’ (London, 1861), 101.

[2] Sir William Besant, ‘Westminster’ (London 1907), 112.

[3] Dr. Crott Auctioneers, Frankfurt. Lot 256, 10 November 2018, sold for 115,200 euros

[4] British Museum Number 1874,0718.48.

[5] John Goldsmith, ‘Does Cromwelliana Exist? A review of personalia associated with Oliver Cromwell’ in Jane Mills, ed., ‘Cromwell’s legacy’ (Manchester, 2012).

[6] British Museum number 1786,0928.1. Jane A Mills, “Cromwell’s Watch: Somewhere in Time” in ‘Cromwelliana, the Journal of the Cromwell Association’, Series II, no.1 (2004), 100ff.

[7] Mercurius Civicus, 11-18 April 1644. Thomason Tracts, British Library, E43(10).

[8] National Archives Pipe Rolls E351/305 and 306. Quoted W. L. F. Nuttall and W. F. L. Nuttall, “Governor John Blackwell: His Life in England and Ireland” in The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography, Apr., 1964, Vol. 88, No. 2 (Apr., 1964), 121-141.

[9] Sir Bernard Burke, ‘A Genealogical and Heraldic Dictionary of the Landed Gentry of Great Britain and Ireland’ part 1, (1862), 44.

[10] Gentleman’s Magazine, December 1808, 1072(illustration), 1074 (text).

[11] Somersetshire Archaeological and Natural History Society Proceedings, volume 60 (1914), p. 101. The Connoisseur, volume 54 (1919), 39.

This article first appeared in Spink Insider Magazine (Winter 2020)